Dog DNA and Humans

Then came Darwin, Mendel, and Watson and Crick. The last century has seen more changes in dog breeding than the past 10 centuries combined. In the 20th century, researchers such as Stockard, Warner and Humphries, and Scott and Fuller undertook hundreds, if not thousands, of experimental crosses. But by the last quarter of the 20th century, large-scale dog genetic projects were gone, largely because dog-breeding studies took too much time, space and money.

A few researchers maintained small genetic projects. Gregory Acland and Gustavo Aguirre were searching for answers to progressive retinal atrophy (PRA) inheritance in dogs. Their pedigree analyses and crosses between breeds showed that several types of PRA existed, most of which were recessively inherited. Breeders clamored for some way to identify carriers, but without information about the dog genome, finding the gene and devising a DNA test was only a dream.

That dream started to materialize when Jasper Rind, a yeast geneticist, became interested in the inheritance of canine behaviors such as herding and swimming and ran into the same roadblock as Acland and Aguirre. But Rind was acquainted with the process of building genetic marker maps, so he assigned his post doc, Elaine Ostrander, to the task of building one for the dog.

Pressing forward

The project began slowly but got a boost in 1996 when Ostrander joined forces with Acland and Aguirre, giving her access to their samples and pedigrees. Their combined efforts produced the first rough map of the dog genome, with 150 markers. It didn’t pinpoint the gene for PRA, but it narrowed down its location to one chromosome.

Funding was still scarce because mice, not dogs, were the accepted animal model for human hereditary disease. That changed in 1998, when researchers discovered the mutation causing narcolepsy in Dobermans. Human narcolepsy researchers used the information from the narcoleptic dogs to better understand the process in people, something mouse research hadn’t provided. If dog genetic research was applicable in this case, why wouldn’t it be applicable in others?

In fact, dogs make ideal candidates for genetic research that can help people. They share many of the same diseases and environmental risk factors as humans, and they have highly distinctive breeds with distinct disease predispositions. Some breeds have been essentially inbred for hundreds of generations, and most dogs come with generations of known pedigrees. These reasons, among others, convinced the National Institute of Health to provide the funding needed to create a complete genome map of the dog.

It was completed ahead of schedule, and as technologies improved, maps based on other dogs were added in a fraction of the time the first map took. By comparing sequences from several dog breeds, researchers have identified 2.5 million places on the genome where changes in a single nucleotide frequency often occur, accounting for the variation we see in dogs. These single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) may soon be available in a public database called “CANMAP.”

Because dogs are more inbred than people, finding individual genes responsible for a disorder is comparatively easy. Generations of inbreeding result in sections consisting of millions of bases of identical DNA within a breed, as compared to only tens of thousands in people. And because breeds descend from only a few founders, a hereditary disorder found in a breed tends to arise from the same mutation in every affected member of that breed. This differs from the case in people, or even mixed breeds, in which it’s possible for diseases that look the same to be caused by different mutations.

By comparing genetic maps from different breeds, researchers estimate how closely breeds are related to one another. This makes it easier to home in on mutations for diseases shared by related breeds because such mutations probably come from the same founding stock. When a similar-appearing disorder occurs in a distantly related breed, it’s more likely to arise from separate mutations. Collie Eye Anomaly, for example, occurs in several related herding breeds. This made it easier for researchers to narrow down the candidate genes to only a few that were shared by four different related breeds with the disorder.

Human-canine DNA

Which brings us back to the gene for PRA. At first glance, dogs with PRA seem to have the same disorder. But Acland and Aguirre’s early research had shown that different breeds get different types of PRA. The gene for the most widespread form of PRA, progressive rod-cone degeneration (prcd), was among the first genetic mutations located in the dog. Since then, DNA tests have been developed for many canine hereditary diseases, including other types of PRA, von Willebrand’s disease, cystinuria, and others. Of course, some tests don’t quite make the list of Nobel Prize eligibility, but they’re still useful – and popular. In fact, some ongoing research is now aimed at finding genes associated with normal conformation differences such as skull and limb length and hair types.

In a few recent studies, the use of SNPs allowed the researchers to pinpoint target genes using just a handful of dogs. In one case, fewer than two dozen dogs were needed to track down the mutation responsible for white coat color in Boxers. It turns out that white Boxers really are different from your average white dog. The white is caused by the same mutation found in people with Waardenburg syndrome, which causes pigment abnormalities and hearing loss. The ability to use just a few dogs to find mutations opens the door for mapping less widespread conditions.

Success is often measured by funding. The AKC Canine Health Foundation and the Morris Animal Foundation both continue to fund genetic studies. Both organizations recently contributed to the $2.2 million needed for startup funds for the Pfizer Canine Comparative Oncology and Genomics Consortium (Pfizer contributed more than $1 million), which is gearing up to collect tissues and fluids from 3,000 dogs over the next three years. And thanks to a grant for $16 million, European researchers have recently organized LUPA, a consortium of 20 universities. They plan to gather DNA samples and health histories from 8,000 dogs, using the data to look for genes for 18 diseases.

Football Dog Treats: Touchdown Tasties

Check out these pawsome football-shaped dog treats Lucy Postins, CEO of The Honest Kitchen, created in honor of game day.

Ingredients

1 cup dehydrated dog food

¼ cup ham, diced

3 tbsp grated American or Cheddar cheese

½ *Avocado, mashed

1 free range egg, lightly beaten

3/4 cup warm filtered water

Directions

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Hydrate the dog food with the warm water and stir. Thoroughly mix in the remaining ingredients to form a batter.

Use your hands to form the mixture into “football” shapes, and place onto a greased or non-stick baking sheet.

Bake in a 350°F oven for 20 minutes.

Cool completely before serving.

Treats can be stored in an airtight container in the fridge.

*Although avocado stones are poisonous to dogs (and the stone as well as the tough skin could potentially be a choking hazard), the flesh itself is fine for occasional feeding in small quantities, and is a great source of natural, healthy oils. Take care to keep avocado skin and stones out of your pet’s reach and dispose of them (as well as other hazardous food scraps like onion and cooked meat bones) in a secure trash can that they can’t easily raid while you’re enjoying the game. Learn about other fruits and vegetables you can feed your dog: Fruits for Dogs, Vegetables for Dogs.

Dog Breeds Susceptible to Bloat

Dogs and Bloat

Symptoms of bloat include a distended abdomen, lethargy, pale gums, abnormally fast heart rate, struggling to breathe and more. The condition can be caused by numerous factors, including eating too fast or exercising before or after a meal. This condition can affect any breed, but large, deep-chested breeds are especially prone to it. These breeds include Labrador retrievers, German shepherds, standard poodles, boxers and others whose chests are deeper than they are wide. If you are concerned about your dog’s susceptibility to bloat, ask your veterinarian for advice on avoiding the condition. If you suspect that your dog has symptoms of bloat, contact your vet, or take your dog to an emergency veterinarian, immediately.

Tips for Newly-Adopted Dog Owners

When you bring home a newly-adopted dog, you can expect her to be confused and unsure of herself for the first few days. If she comes from a shelter, she might not have experienced the same type of lifestyle that she finds in your home and could be overwhelmed and nervous. Find out as much information as possible about her former life, her behavior and personality. Expect that it will take a few weeks or possibly months before she settles down and regains her confidence.

A Safe Space

Give the dog her own safe space by providing her with a bed in a corner of the house that is peaceful and quiet. Show her that it is hers by giving her a treat in the bed and spend time sitting there with her. Each time you take her to the bed, give her the command by saying the word “bed” and reward her when she gets into it. Prevent children and other pets from interfering with her when she is in the bed, so that she learns it is a refuge when she needs one.

Feeding Time

Feed the dog the same food she has been eating, if possible. If you don’t know what she has been getting, start her off with good quality kibble in small quantities to avoid an upset stomach. If she is underweight, feed her four small meals a day instead of two large meals for the first month to help her digest the food and to prevent her from overeating. Provide plenty of fresh water at all times and watch her carefully for any signs of vomiting or diarrhea. Once she is eating the food without any side effects, you can gradually introduce treats and home-cooked dog food, if you prefer.

House Training

If your newly-adopted dog has lived most of her life outdoors or in a cage, she might not understand that she can’t soil where she sleeps. Anticipate her needs and take her outside immediately after she wakes up in the morning, directly after meals and last thing before bedtime. If she is a puppy or older than 7 years, she may need to go more often. Wait outside until she eliminates, then praise her enthusiastically every time. If she has an accident indoors, ignore it and clean it up with an enzymatic cleaner to remove the smell. Avoid punishing her, because she may not understand that she has done wrong and it will confuse her.

Preventing Anxiety

Your newly-adopted dog might bond with you so well that she becomes terrified of losing you. This could take the form of separation anxiety, which manifests in destructive behavior, excessive barking, soiling or even aggression towards family members and other animals. Begin leaving the dog alone for short periods of time soon after you bring her home, so she becomes accustomed to you leaving and returning.

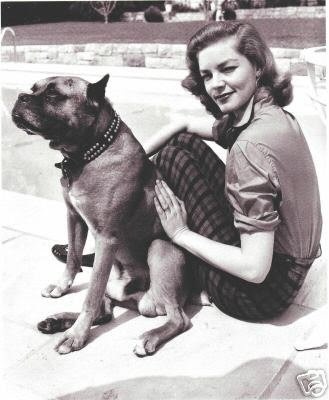

Lauren Bacall, Actress and Dog Lover, Dies at Age 89

A star of Hollywood’s golden age, Lauren Bacall, died in New York City on Tuesday. Bacall was known for many memorable roles, co-starring many times with her husband, Humphrey Bogart in movies such as “The Big Sleep,” “How to Marry a Millionaire,” “Designing Woman,” “Key Largo” and “The Mirror Has Two Faces,” for which she was nominated for an Academy Award.

Besides her beauty and talent, the actress was well known for her love of dogs. In many photos throughout their lives, Bacall and Bogart were seen with their many dogs.

In an interview with NBC New York, Bacall’s neighbor Bill Karam, spoke of interactions with Barcall and his dogs. “She said to me, in this deep voice, ‘What’s your dog’s name? I said, ‘Blanche.’ And she said, ‘Miss Dubois?'” Karam said he last saw her about three months ago and she immediately recognized his dog. “She was always engaging with the dogs. She loved her dogs,” he says.

In 2008, Glenn Close visited Bacall and interviewed her about her love of dogs, specifically her Papillon Sophie.

“I was always a dog yearner. I didn’t have a dog growing up in the city with a working mother. As an only child, I yearned for someone to talk to,” Bacall tells Glen Close in an interview on BogieOnline. “When I was sixteen, we got a champagne-colored Cocker Spaniel and named him “Droopy.” He was very male. From the first moment, he was very possessive of me. All my dogs have been possessive of me. We eventually mated Droopy and kept one of his girl puppies—Puddle. I went to Los Angeles for a screen test when I was eighteen years old. My mother followed me out later. The dogs came, too.”

We have compiled a collection of our favorite photos of the late glamorous actress, who truly knew what it meant to be a movie star.

ACertainCinema

Jake-Weird

DailyMail

PuppyLovePreSchool

Pets4Ever

WideningCircle

CashmereJeans

Zimbio

She will be dearly missed by many, but she will surely be met by many wagging tails.

Dogs That Dig Furniture

The ancestors of our modern dogs had no comfy beds or couches to lounge on, of course, so when they wanted a comfortable spot to lounge, they’d simply make one.

Dogs today retain the instinct to do that. Dogs who spend time outdoors will dig a nest-like depression in the soil or dry grass that comfortably fits their body contours, and lounge there, alternately napping and surveying their territory.

Why a digging dog can be a problem

When indoors, this instinct is still active, and dogs will try to arrange the surface where they wish to lounge to fit their body. If this means digging a hole in the seat of your brand new lounge chair, the cost to repair or replace that cushion will never even enter your dog’s mind.

How to live with a dog that digs

One possible answer is obvious – keep the dog off the furniture, period. Provide your dog with her own personal blankets and pillows that you do not mind getting ruffled up.

If you wish to allow your digging dog to share your comfy furniture, but don’t want her to dig into it, lay a blanket or other durable fabric on the seat, with the edges tucked down around the sides of the cushion. When your dog indulges her instinct to dig a nest, she will untuck the blanket and rumple it up, instead of trying to dislodge and rumple the upholstery.

Flying With Dogs

“Everyone within a mile of us is now hearing the frantic barking of what appears to be a completely insane Tasmanian devil disguised as a Min Pin. She was barking like she was going to attack someone — anyone,” recalls a mortified Christner. Her foster dog crooned at her feet throughout the flight — despite medications approved by her veterinarian, but often discouraged by others, including the American Veterinary Medical Association.

“She barked and clawed at the [bag’s] netting to actually make a hole so she could stick her head through,” Christner says. Ignoring a chew toy, the pooch “chewed on my shoe.”

The experience taught Christner some lessons about the right and wrong way to pursue canine air travel — a subject that divides animal lovers.

To fly or not to fly?

Breeders and dog fanciers routinely fly dogs without trouble. Airlines assert that air travel is safe for dogs, as does the Air Transport Association of America. But American Kennel Club spokesperson Lisa Peterson adds a caveat: “We certainly believe it’s safe to fly with your dog on any commercial airline flight, provided the owner takes certain pre-flight precautions.”

Several humane organizations and some veterinarians warn of hazards for dogs in the cargo holds of planes, citing incidences of dogs injuring themselves as they claw at the crate to try to escape or escaping when crates open accidentally on a tarmac. Don’t fly pets if possible, especially if the pet isn’t small enough to fit in a carry-on kennel you can take into the cabin, advise the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and the Humane Society of the United States.

Since record-keeping by the U.S. Department of Transportation began in May 2005, 30 pets became injured during air transport, 17 pets became lost and 49 pets died, according to a DOG FANCY review of federal records as of March 2007.

“I much prefer having the dogs travel with the owner inside a car or van because they can take breaks when appropriate, stretch their legs, and are being handled by people who know and love them,” advises Texas A&M University animal behaviorist Bonnie Beaver, DVM, American College of Veterinary Behaviorists diplomate, and past president of the American Veterinary Medical Association. “While many dogs travel successfully by air, I know of the horror stories where problems occurred.”

But, recognizing flying is sometimes unavoidable, experts advise that there is a lot to think about if you’re going to try it.

Practical advice

1. Definitely fly your puppy in the cabin as you coo and feed him tiny treats like beef extract on the tip of your finger, advises Tufts University veterinary behaviorist Nicholas Dodman, BVMS, a diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Anesthesiologists and the American College of Veterinary Behaviorists.

For a young pup during the crucial formative time in his life, being jostled in a cargo hold as a noisy plane takes off and lands is akin to taking Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride at a theme park. Any “horrendous experience,” Dodman says, “can have long-lasting, lifetime effects.”

2. Choose the quickest direct early-morning or evening flight to ensure your dog travels when temperatures are favorable in the cargo hold and on the tarmac — and fly direct to ensure he doesn’t end up in a different city from you. Avoid flying during extreme weather — hot or cold.

“In general, I discourage people from flying with dogs that cannot actually be in the cabin with them,” Beaver says. “There are air traffic delays that can become real problems, and I certainly discourage dogs from flying if there is not a direct connection from origin to destination. Humans have enough problems making connections.”

3. When buying a crate or kennel, be sure it’s large enough for your dog to stand up, turn around, and lie down in. Look for a sturdy one with locking bolts and strong metal doors. The strongest have four metal rods that fasten the door to the container, the federal government says. Further secure the door by adding tie wraps that can be cut in an emergency.

Many injuries, deaths, and escapes happen when dogs chew their way out of a plastic crate, push the door open, or take advantage of a broken or improperly latched lock. For example, a Golden Retriever named Skipper “lost teeth, cut his gums, and lost toe nails” as he chewed and scratched to try to get out of his kennel during a cross-country flight to Seattle in June 2006, according to a Continental Airlines report to the federal government. When another dog — a Greyhound named Gianna — arrived on a December 2006 Alaska Airlines flight to Seattle, she was discovered with her mouth and jaw stuck on the front gate of her kennel.

4. At home, get your pet accustomed to the travel carrier or kennel for at least one month, lest he put up a fight like Christner’s Cricket.

Joan Carlson, executive director of Florida’s Humane Society of Vero Beach & Indian River County, took deliberate steps to acclimate her cousin’s new mixed-breed puppy, Little Bella, for a flight from Orlando to Philadelphia: She put special treats and toys in the carrier, as well as Bella’s meals. She let Bella walk in and out of the carrier at will. Gradually, as days wore on, Carlson closed the carrier to make Bella stay inside for a short time, then increasingly longer periods. Carlson eventually took Bella in the carrier on a short car ride to get her accustomed to the idea of motion. When the pair finally flew, Bella “was a little whiny at first,” Carlson says, but “it was her safe place. It was very easy to adapt to being in a crate and being on a plane.”

5. Don’t assume your pet will be accepted on the flight. Reserve a space for your dog — whether he travels in the cabin or in the cargo hold. Airlines have limited spots for animals.

6. Be sure your dog is fit to travel by getting him checked by a veterinarian a week to 10 days before your trip, as airlines require. Realize that pre-existing conditions could become a problem anyway. For instance, older dogs can have borderline kidney disease without their owners realizing it. They compensate by drinking lots of water, Dodman says. If such a dog gets on an airplane without free access to water, Dodman says, “you can precipitate renal failure.”

7. Don’t feed your dog for four to six hours before flight time, HSUS advises. A small amount of water before the trip is OK. Freeze a margarine tub filled with water and place that ice — not water — in the kennel’s water tray. That way, water won’t dump into the kennel and onto your pet, but hydration will be available as the ice melts.

8. On your dog’s collar, attach two pieces of identification — a permanent ID with your name and home address, and a temporary ID with the phone number where you can be reached during your travels. Also helpful: a microchip or tattoo as permanent ID. The more ID, the better.

Know your dog

As with many situations, it’s important to trust your gut when considering flying your dog. If you suspect your dog is a nervous Nellie who couldn’t take the flight, you’re probably right.

The drug maker Novartis Animal Health estimates that 15 percent of dogs suffer from some degree of separation anxiety, which, Dodman says, makes them poorer flight candidates. “Those dogs can’t be left alone,” he says. “They can actually chew through metal. They’re like Houdini dogs.”

Christner, for one, says her foster dog, Cricket, won’t be taking another plane trip. “I don’t think she was cut out to fly. She did not like to be confined and it made her crazy,” she says. Unless her name has been blacklisted after the Cricket fiasco, Christner says she will continue to travel with her other two dogs, “as they are true travelers.”